As I was on holiday in France this piece was filed too late for publication in The Spectator, so I’ve posted it here – AFH

The only remarkable thing about Richard III is how unremarkable he was…

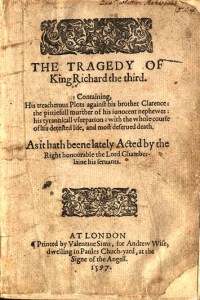

Watching the reburial of King Richard III, this writer was struck by how the unearthing of his bones was being sold to those who would buy it as the unearthing of the ‘truth’ about a much maligned monarch. Conversely, Shakespeare’s play of the same name was being touted as the very zenith of propaganda and the Bard of Avon himself as a sort of Goebbels with the tongue of Goethe; history’s most gifted author prostituting his talents to defame the last and most discrete of its true kings, the Plantagenets, to justify the brash and barbaric usurpers who followed, the Tudors.

I myself, attempting to judge events in the context of the time, take the view that the Duke of Gloucester – the name by which he was most commonly known, having held the title from age 9 – was nothing more than a minor product of those crude times whose only notability lay in providing inspiration for one of our greatest artist’s first decent works and through that stabilising a nation that had suffered two generations of civil war. In death and dramatic ignominy Gloucester achieved more for his country than his rather prosaic savagery did in life.

The first point to be made is that there isn’t a historian worth the name who doesn’t hold Gloucester responsible for the death of his nephews – the 12-year-old King Edward V and his younger brother Richard, 4th Duke of York – the ‘Princes in the Tower’.

On the death of Gloucester’s eldest brother, King Edward IV, Gloucester became Lord Protector and had the princes sent to the Tower of London “for their own safety”. He then announced that young Edward V’s coronation would be delayed, and not long afterwards the children were proclaimed illegitimate due to their father’s alleged bigamy. Two weeks later – 6th July 1483 – Gloucester was crowned King of England and France (and Lord of Ireland.) The princes were neither seen nor heard from again.

It is undeniable that their lives weakened Gloucester’s throne – an armed attempt was made to free them from the tower that July – but the rumours of their murder, which started early in his 777 day reign, had a similar destabilising effect. As such, Gloucester profited from their death – their alleged illegitimacy could be easily reversed, as indeed it was, post mortem, by Henry Tudor who married their sister and called Edward his predecessor – but would have profited much further had he made any vaguely plausible denial or produced evidence of another’s guilt. There was none.

The only other man accused of their murder by contemporary or immediately subsequent accounts – Mancini, Lopes de Chaves, More, Vergil, Holinshed – was Gloucester’s creature Buckingham. If he wasn’t acting on Gloucester’s orders, how did he gain access to the closely guarded princes? Or how could anyone else? And if it was Buckingham, why didn’t it form part of his trial for treason and subsequent execution that winter? Why no investigation at all after their disappearance?

However, more important than this act of murder, is how unimportant it really was. I realise that in our gentle age the killing of your pre-pubescent nephews to secure your throne may seem a rather unforgiveable action, and even then it was seen as a little beyond the pale, but with a little liberalism of mind – of the sort championed by Isaiah Berlin about using “imaginative insight” to understand far distant eras and cultures – one can see how it happened.

Remember that Gloucester’s entire family had been slaughtering one another and everyone else for the crown for quite some time, starting with his paternal grandfather, the 2nd Duke of York, who was executed for treason by his cousin Henry V.

(By way of family tree: The 1st Duke of York was King Edward III’s fourth son. Edward III’s third son was John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster. This is the origin of these warring cadet branches. The eldest son was the Black Prince, who died before succeeding, so his son became King Richard II who was deposed, imprisoned and starved to death by Henry Bolingbroke, later King Henry IV, father of Henry V.)

Gloucester was himself the fourth son of the 3rd Duke of York, who allied with his brother-in-law Salisbury and rose against Henry V’s son Henry VI. Both died in battle as did Gloucester’s older brother Rutland. York’s eldest son rose to the throne as Edward IV, murdering his second cousin Henry IV to do so, and while on the throne had another brother, George, Duke of Clarence, executed by drowning him in a butt of Malmsey wine. This was, it should be said, Clarence’s second betrayal of him.

Gloucester himself fought hand-to-hand in midst of various battles and was wounded in one of his first at Barnet aged eighteen. A more morally hardening experience than a medieval battle it is hard to imagine, with the stench of opened guts – vomitous, faeces and blood – and the relentless screaming of slow death without analgesia. Gloucester’s final moments as king were spent trying to personally hack his way through Henry Tudor’s bodyguard to get at the man himself, whilst slowly being sliced to pieces himself, according the surgeon who examined his bones, until the coup de grace in which his skull was completely opened by a halberd.

These were not gentle souls nor did they live in gentle times. The idea that such a man would regard the killing of his nephews as particularly grave is unrealistic. The idea that, should he feel the need for chivalric or religious reasons, he couldn’t justify it to himself to bring an end to almost three decades of civil war tearing the country apart is absurd. The Wars of the Roses began with a child king, Henry VI, who lost the Hundred Years War and flooded a bankrupted country by men trained for little but war. Gloucester was trying to prevent a repeat.

No, what is most notable about the ‘Princes in the Tower’ is the not the slaughter of innocents, but that Shakespeare regarded that as not nearly enough to besmirch Gloucester’s reputation. So he added to his butcher’s bill the murder of Henry VI, Henry VI’s son and heir Edward of Westminster, Gloucester’s own brother Clarence and Gloucester’s own wife Anne, and pretty much anyone else he laid his hands on. He needed to show him to be a “bloody tyrant and a homicide; / One raised in blood, and one in blood established.” Double infanticide, even nepotistic infanticide, was insufficient to the task. He even took a mild difference in shoulder height caused by spinal curvature – something most likely not noticed until he was paraded naked after his death – and multiplied it into a hunchback, withered arm and club foot, defects which would have hampered the very combat skills which are one of his sole claims to notability as king (and which Shakespeare himself acknowledged.)

And how could mere child murder be enough? Shakespeare’s own monarch, Elizabeth, wasn’t beyond killing relatives – as Mary, Queen of Scots found out – and her grandfather Henry Tudor, later King Henry VII, who comes out of Shakespeare’s play as a saint, immediately imprisoned the late Clarence’s ten year old son Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick – the last legitimate male of the House – in the tower, and when he was executed fifteen years later he had been so long incarcerated that he was described as being unable to “discern a Goose from a Capon.” As for his son King Henry VIII, the man early abandoned God and common humanity, beheading the woman he so much loved he left his wife and church for her, to maintain power.

(I must admit a personal grudge there: the Duke of Clarence’s eldest child, Edward Warwick’s older sister, Margaret, Countess of Salisbury is my own forebear and was the last person alive to have held the Plantagenet name. She was executed by Henry VIII, and particularly badly so. An elderly lady, she had to be held down and even then the first stroke was to the shoulder not the neck and a further ten blows were required. One of the 150 witnesses said she made a run for it and was pursued screaming and bleeding until she was finally cut down. She was later beatified and made a martyr of the Catholic Church.)

By modern ethical standards, there were no good kings in the Middle Ages. However, what really mattered in those days, as it still to some extent does, was stability and continuity: il principe‘s warrant proceeds from his ability to mantenere lo stato , in Machiavelli’s words. Any revolution that succeeds is justified by its own success as the old Leviathan has lost the power to hold the ring and keep its people out of the state “war as is of every man against every man” – bellum omnium contra omnes – in Hobbesian terms.

Gloucester failed to deliver this in life, but by forming of the foundational myth of the Tudors, in death he served the great purpose of ending the horrors of civil war. Between his savage but largely blank canvas, and Shakespeare’s singular literary gifts, he bequeathed a peaceful realm. For that it was worth digging him up, and burying him once again. Let’s just not pretend that the deliberate consequences of actions were of any great note, nor his behaviour of any singular virtue, nor his legacy anything other than as a rather dark stepping stone on to more successful sovereigns.

Alexander Fiske-Harrison