The original article at full length can be found for subscribers at The Telegraph online here.

When I first came to Bad Gastein, a year ago, I could not believe that I had not only never been here before, but had never even heard of it. The vagaries of its notability in history are almost as cyclical as the rise and fall of stock markets.

In February 2020, it seemed to me a classic bustling ski resort, with extraordinary, high-level skiing, comprising 200km of pistes, half of them red runs. Admittedly, the languages you heard in the après-ski establishments tended more towards the Germanic than the frequent smatterings of English or French one might hear in Zermatt or Val d’Isère.

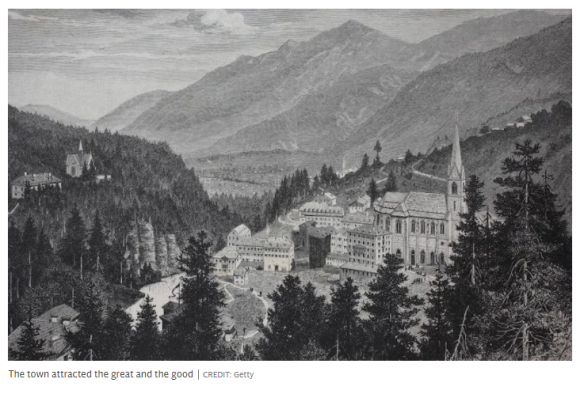

However, what really struck me was the look of the town. Built into the steep mountain slopes, its vertiginous streets are lined with exquisite fin de siècle houses from the heyday of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Even the train station – 90 minutes to Salzburg, 3 hours to Munich – is an Art Deco gem, opened by Emperor Franz Joseph himself in 1905, the first such station in the Eastern Alps.

For this was the Imperial resort. The Prussian Kaisers would come and meet their Habsburg Emperor cousins here to enjoy the waters and the walking, for both of which it had been famed since the 7th century. Of course, in those pre-skiing days, summer was the high season.

For this was the Imperial resort. The Prussian Kaisers would come and meet their Habsburg Emperor cousins here to enjoy the waters and the walking, for both of which it had been famed since the 7th century. Of course, in those pre-skiing days, summer was the high season.

As American travel writer Helen Hunt Jackson put it a century and a half ago: “The most experienced traveller in the world will have telegraphed beforehand for rooms, having read that Wildbad-Gastein in August is so crowded with the nobility of Russia, Germany and Austria that it is not safe to go there without this precaution. As he steps out of his carriage in front of Straubinger’s Hotel, Gustav, the pompous head-waiter, will wave him back, and explain with much flourish that there is not so much as one square inch of unoccupied room under his roof… Lord A- is coming for a month, Count B when the Prince, or Duke, or Herr, has claims on yet another.”

Of course, after the nobility came the art crowd – with breaks for world wars – so at the long bar of the old hotel, the Salzburger Hof, you will find photos of former guests: Einstein and Freud, Thomas Mann and Somerset Maugham, Douglas Fairbanks junior and Tyrone Power.

However, as the summer crowds faded along with the medical fad of radon-infused water, this Monaco of the Alps, as it was known, faded from memory into obscurity, leaving the beautiful buildings untouched, the view of the city a historic gem preserved in unprofitable aspic.

The fashion for skiing brought it back into the black, and the investment in infrastructure led to the Alpine World Ski Championships first coming here in 1958. The high season shifted to winter as the sport changed from a luxury pursuit to a pastime 72 million Europeans – one in six of us – indulged in in 2020.

Yet, stepping off that same old-fashioned train on Sunday, I found myself in a different world, an unnervingly unpopulated set of streets. In the NATO counter-terrorism handbook, under the heading ‘Advanced Situational Awareness Training’, they speak of “the absence of the normal and presence of the abnormal” as signals of something about to happen, and that was how the town felt. As though Soviet tanks might roll through at any moment and the populace have fled. This tangible silence is what the governmental reaction to the novel coronavirus has done, although what it has really done to the livelihoods of the 4,500-souls who live here is far more pernicious and, for now, far less visible.

Austria is still in lockdown, but exercise is encouraged, and so the slopes remain open, and whilst it would be nice to say what a pleasure it was to have the piste to myself, to glide and slide over the untrammelled white slopes, I could not ignore the niggling sense of conscience. As the ever-reliable Johann Schober of Sport Schober said, only half joking, as I rented my skis from him, “I have not skied this much in 50 years. And I do not mean this in a good way. I may be fitter, but I am also thinner because there is less money for food for the table as well.”

It feels unusual to say that not having to queue for a ski lift felt bad, but it genuinely did.

There is, though, light at the end of the tunnel, or, to put it another way, the wheel turns and die Wildbad Gastein, ‘the wild spa of dark waters’ – the half kilometre of rapids and falls running through the centre of town are stunning – will always return to the top.

By coincidence, on the day I arrived last year, I was taken by my fiancée Klarina, who grew up here, to the Straubingerplatz, to which she referred as the “ghost town”. For it was there in her youth that the teenagers gathered in front of the oldest and grandest hotel, which even then had been shuttered and closed for decades, despite its stunning façade and the fact that the wild waters ran literally down the side of the building itself.

Having viewed what I perceived as the travel writer’s equivalent of The Decline and Fall Of The (Holy) Roman Empire, I saw in the newspapers that a decade long argument about who actually owned the hotel and its surrounding structures had been resolved by the region itself, Land Salzburg, which had bought it outright, and had done a preliminary deal with a German hotelier from Munich – as I said, three hours up the train-tracks, and a massive provider of the tourists who come nowadays – to restore the jewels in the crown of Gastein and its environs, to the tune of half a hundred million Euros.

So, having arrived now, when that sense of ghostliness had spread to encompass the entire town, I saw in the local paper that the town council would be discussing this very matter, I got myself on to the Zoom meeting in which the future of this place was determined. Will Gastein sink into its old, wild waters, or will it, once again, rise up and swim?

The German hotelier in question, Dr Christian Hirmer, is a mild-mannered young man for a third-generation clothing magnate, whose moves into everything from real estate to hospitality have left impressive marks. However, my worry was, given that every shop, hotel and office he owned had been closed by Covid, whether he would still be willing to commit to the revivification of this old Imperial resort.

The answer was an impressive and resounding yes. Tens of millions of Euros are being funnelled through building contractors and local and regional government, guided by the vision of BWM architects from Vienna, to recreate the grandeur of old Gastein, while adding the modern touch of comfort and profitability.

Yes, to create the latter, a small tower must be added behind the old Straubinger, but who can complain about a roof-top infinity pool looking down onto a waterfall, or a skylit tunnel between the hotel and the ski-lifts to circumvent the steep slopes one faces just to get to the cable car. And while in any town this historic, there will always be nay-sayers about change, the fact that the tower is coloured and shaded so as to practically fade into the scenery shows a rare sensitivity, camouflaged in its context.

Indeed, in order to put itself back up among the first rank of such resorts, to outdo those who once outstripped Gastein like the younger but more glamorous – for now – Swiss resort of St Moritz and nearby Kitzbühel, they are even arranging the first ever Imperial Snow Polo Cup at Sport Gastein to open the winter season, with a host of royalty on the guest list; fixers from that world like Major Peter Hunter of Guards Polo Club from England and International Polo Events, and sponsorship being discussed between the incoming Hirmer Group and that other Grande Dame of Austrian hotels, The Imperial in Vienna.

Until then, I was perfectly happy to stay at the excellent Boutique Hotel Lindenhoff, the only hostelry of quality with the courage to remain open in these troubled and troubling times.

THE TELEGRAPH

TRAVEL

Once the ‘Monaco of the Alps’, this forgotten spa town is poised for a comeback

Bad Gastein, now eerily quiet, was a magnet for high society during the Austro-Hungarian Empire